Weatherwise/Otherwise: Artists Respond to Climate Change, at Dalton Gallery of Agnes Scott College through December 9, had turned prophetic by the time of its opening in September. Curator Dorothy Moye had chosen as its central artwork Mary Edna Fraser’s Charleston Airborne Flooded (South Carolina), a large batik wall hanging depicting an aerial map of Charleston and environs flooded in an era of rising oceans. The hurricane which caused flooding on the South Carolina coastline actually submerged, temporarily, an even larger land area.

This unexpected meeting of fact and abstraction was a boost in instant relevance for a show that confronts a major conceptual problem: namely, that the currents of climate that create weather conditions are too big to fit comfortably into our everyday mental categories. The visible effects are dependent on invisible combinations of evaporation, condensation and atmospheric pressure that constitute what theorist-philosopher Timothy Morton calls a “hyperobject” — a single entity so vast and so amorphous at the literal and metaphoric edges that its details forever threaten to elude our verbal definitions and our methods of investigation. The planet-wide systems we call climate and weather are about as hyper as things get within the Earth’s gravitational field.

The show itself is something of a miniaturized hyperobject, in the sense that it simultaneously tries to educate about climate change and educate about the many ways in which experimental photographic and craft-based art can analyze and communicate — in this case, about the topic of climate change. Nothing less would be expected from the curator who originated the ambitious and nationally respected annual juried exhibition of experimental artists’ books at the Decatur Book Festival, but it means the show reveals its dual purpose only slowly. It requires time to absorb its lessons.

Find original art at www.saccoart.com

Beautiful but bewilderingly complex, Nathalie Miebach’s immense wall pieces are composed of woven colour-coded strips containing numbers, symbols and different ways of organising them. They reflect data regarding temperature ranges over time periods, and the rhythms of change thus visually expressed can also translate into musical scores, compositions that Miebach has performed as a different way of making invisible processes and numerical relationships into works of art. Sibling Rivalry is probably the most complicated of the visual works, a rendition of hurricane data in terms of galloping racehorses bearing numbers, ships with furled or billowing sails and racks of lettered dominoes arranged by decades: 1950, 1960, 1970. . . . A glossary of symbols is necessary to translate these pieces out of private mythology and back into intelligible allegory, and Miebach provides one.

The same dilemma afflicts Bettina Matzkuhn’s embroidered-linen Schmetterlinge “butterfly” maps of weather systems (not merely a visual metaphor, the butterfly shape presents the continents without distorting their relative sizes). An accompanying video, The Zoology of Weather, explains what is represented in images that otherwise would be beautiful but conceptually opaque. As the artist explains how her artworks relate to the way in which weather systems operate, she remarks, “The big picture spans more than the eye can see.”

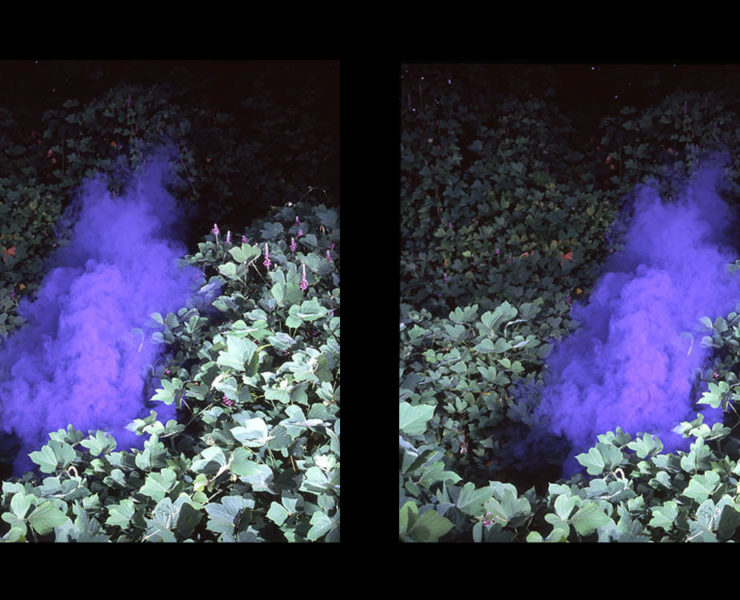

Peter Bahouth’s stereoscopic photographs, VENT: a photographic response to the heat and pressure we put on the planet, also use metaphors and analogies to depict the disturbances in our planetary weather. His landscapes “vent” or “let off steam” in actual clouds of gas or mist symbolizing the response from an angry planet to the stresses our environmental depredations have placed upon it.

Karen Reese Tunnell’s work also leaves implicit the relationship between turbulent atmospheric conditions and climate change, but her marbled paper collages of types of cloud formation are remarkable works of art, and her titles and captions are educational explications of atmospheric dynamics from the newly named Asperitas (Latin for “roughness”) to the witty Cumulus Granitus (about which Reese comments, “Pilot terminology for actual mountain peaks that are indistinguishable from clouds; a dangerous condition.”)